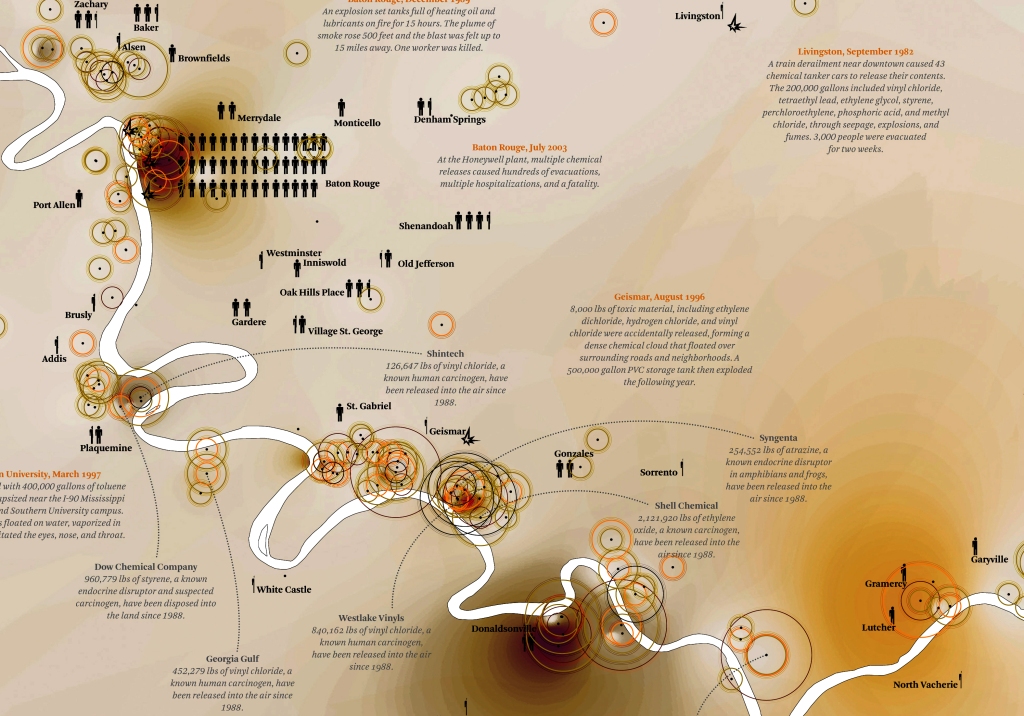

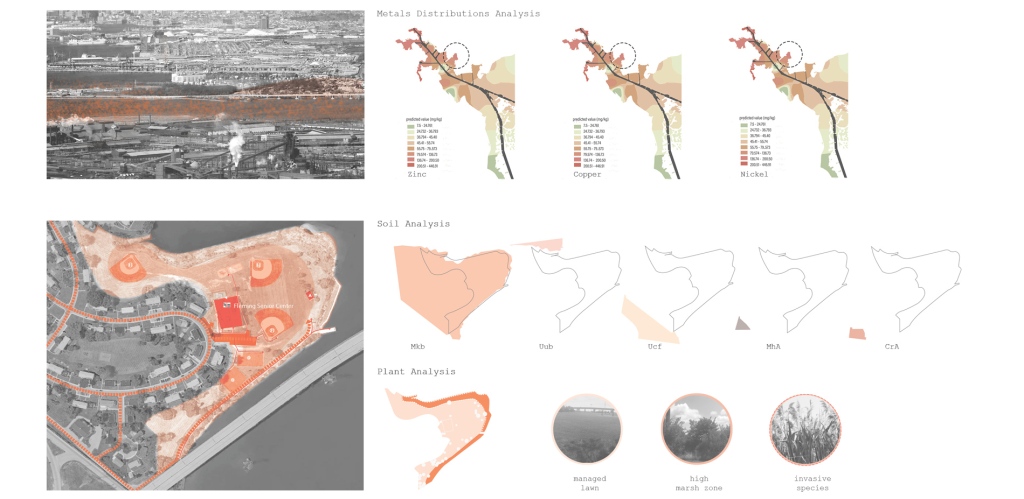

Have we reached a post-landscape condition? Have new designs, representations and physical forms been realized which provide for collective actions and alternative relations with where we live, work and visit? In Recovering Landscape, Corner describes his inspiration for advocating a ‘recovery’ of landscape as ‘less the pastoralism of previous landscape formations’ but instead the ‘yet-to-be disclosed potentials of landscape ideas and practices’. But as economic and political contexts shifted, during the global economic collapse and the subsequent recession, can we identify an emergence of alternative practices and landscape forms? Concerns for ecological restoration and programmatic approaches to landscapes are emphasized by Corner whose Field Operations designed the master-plan for New York’s Fresh Kills Park and realized the rehabilitation of the High Line as a public park. However, Corner describes that ‘massive process[es] of deindustrialization’ have placed new complex demands on land-use planning requiring the ‘accommodation of multiple, often irreconcilable conflicts’. Landscape projects that remediate and repurpose polluted post-industrial sites have gained currency in urban redevelopments, building on the work of land artists Such as Mel Chin, and landscape architects like Peter Latz. But while we can identify inventive approaches that decontaminate formerly abandoned landscapes, few contemporary landscapes or urban design projects have confronted their contribution to increasing land-values, displacement of remaining industries and aggressive gentrification. Environmental recovery of landscapes facilitates urban redevelopment, provides a foundation for spatially and aesthetically reproducing cities and furthers opportunities for economic returns for individuals and organizations that own brownfield sites. Projects improve ecological conditions but fail to address, and in many cases exacerbate, businesses displaced, jobs lost and individuals excluded from renewed urban areas. While in some cases, as Cosgrove claims of recent critical thinking, ‘landscape is approached as a spatial, environmental, and social concept rather than as a primarily aesthetic term’, prevailing landscape practices remain tied to economic priorities. And although Corner reminds us that landscape is inextricably ‘bound into the marketplace’ neither his writing nor his landscape practice provide clues for how these relations can be uncoupled or rethought.

Ed Wall, Post-Landscape or the Potential of other Relations with the Land (2018)

Hoerr Schaudt, Rooftop Haven for Urban Agriculture at Gary Comer Youth Center (2009)

![Prepositions [sic]](https://landscapetheory1.files.wordpress.com/2017/01/b6e7ce43d1c8988f005ce3562c4ec380_2048w.jpg?w=825&h=510&crop=1)