Large Parks on disturbed sites should be recognized as landscapes of consumption as well as production. It is tempting for designers of large parks built on abandoned industrial sites to heroize the buildings and machines that remain. Such strategies, however, privilege the histories of production over the histories of consumption that are also embedded in such sites. This allows visitors to distance themselves from the histories of human, material, and chemical flows on and off the site, and to limit their own culpability in and responsibility for such histories. (“Malevolent industrials polluted the air and water, not my ancestors and certainly not me.”)

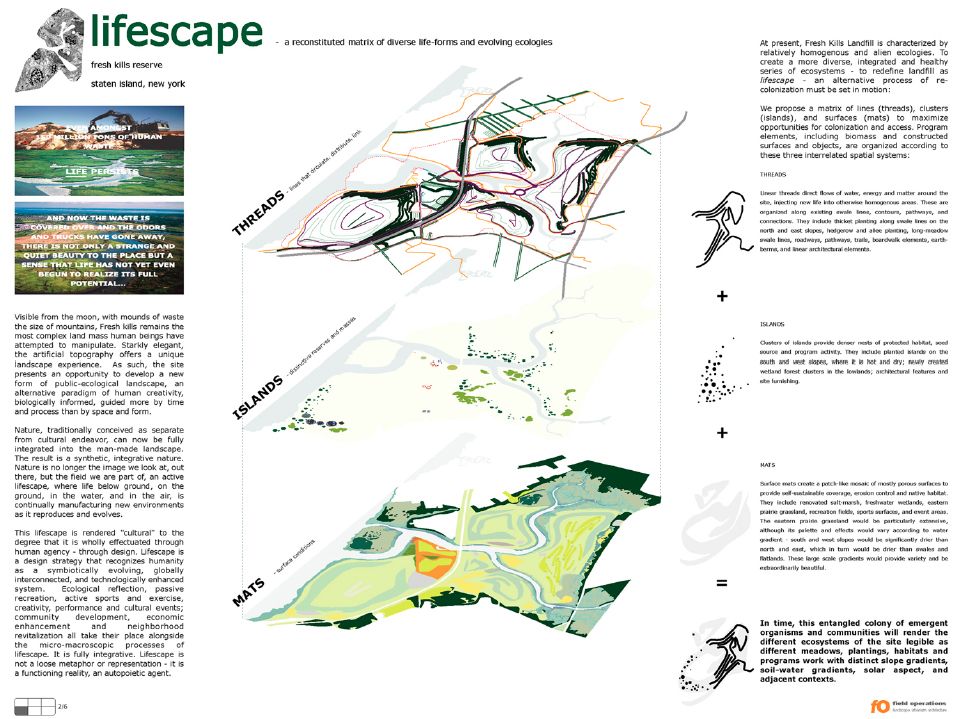

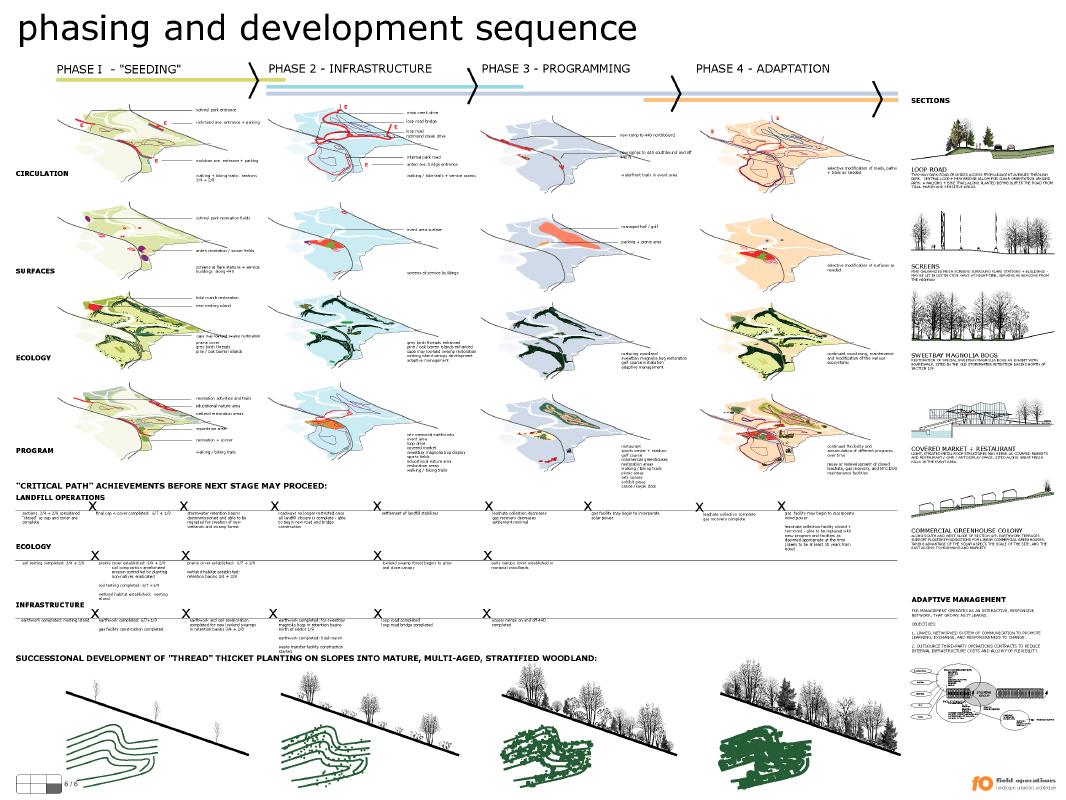

Similarly, design strategies that focus primarily on the ecological processes of remediating a toxic industrial site fail to account for the intermingling of the natural, social, and industrial processes that permeate such sites. Forest, earth, and rivers are processed into lumber, ore, and water that are the raw materials for industrial production. The results of the processes are consumer goods and emissions into the ground and waterways. Technology doesn’t simply transform nature into commodities, it cycles back new and often toxic byproducts into nature. Thinking about landscapes on consumption and production requires thinking of the circulation of need, desire, material, goods, energy, and waste across disciplinary categories such as nature and culture, ecology and technology, and even public and private. We need design strategies that make visible the past connections between individual human behavior, collective identity, and these larger industrial and ecological processes.

A timescape conception of large parks leads to a recognition of uncertain sites-spaces where matter, flow, and waste know no boundaries -and to a different conception of consumer society.

Toxic discourse is an expression of a collectivity of consumer-citizens who perceive their environment through the lens of uncertainty and risk. Disturbed sites are byproducts of economic policies that viewed nature as a resource and that accepted environmental degradation as the inevitable consequence of technological progress. The experience of designed landscapes on and in disturbed sites can render visible the consequences of the economic, political, and social decisions that led to those risks.

Elizabeth K.Meyer, Uncertain Parks: Disturbed Sites, Citizens and Risk Society. (2007)

HOSPER Landscape Architecture and Urban Design, GENK C-m!ne (2012)