- Just as a landscape is a way in which people and place relate, making landscapes is unavoidably a political activity because implicit in the transformation people bring to a place is the way people are organized in order to do this. However, the set of representations used to create landscapes tends to eclipse the political dimension.

- Landscapes created through representation propose and legitimize the ways people and places are associated, which are susceptible to be used as instruments for convincing and propaganda for policies that were formulated prior to them.

- Metropolises come with the presumption (where the interest of institutions and landscape makers converge) that people are not capable of expressing themselves or relating to each other in them, that they are only the sum of unrelated individuals who do not know how to behave in the new landscapes of the city.

- Point 3 leads to the conviction of understanding public space as a place in which to adapt people to the new landscapes of the city through education. However, it is actually in the pursuit of this objective that the need is seen to erase the cultural baggage these people have, so that they can be taught to fit into the previously represented landscapes of the city’s large green spaces.

- The education project shown in Point 4 often produces political conflicts between people and the institution of public space, in which the landscape maker plays a role, no longer of educator, but of integrator of the many discourses of the people in them which are compatible with the one that institutions advocate.

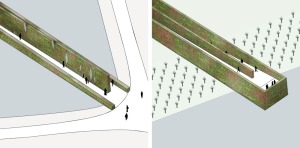

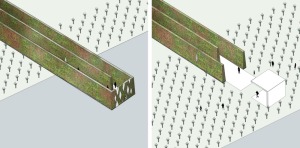

- Some creators have thought about using the landscape not to mute or to educate, but on the contrary, to encourage people to express themselves. In such processes, the change in discourse changes the way in which we perceive landscapes.

- Paradoxically, the conversion of the city into an exhibition space for the urban spectacle opens spaces where new languages can become visible when the spectacle ages or deteriorates. The city of exhibition becomes volatile and even fragile if its discourse is not constantly nourished.

- While landscape has been used as an instrument of conviction and controlling discourse, a way of thinking is being formulated that tends towards the democratizing potential of landscape. This will lead to a new figure of landscape maker in a process which we will continue to study.

Victor Ténez Ybern, Notes on the Politics of Landscape (2016)

Coloco, Asfalto mon Amour (2013)

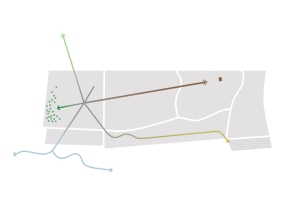

FIND IT ON THE MAP