Judith Stilgenbauer, Processcapes: Dynamic Placemaking (2015)

Peter Walker + PWP Landscape Architecture, Hilton Hotel (former Kempinski) Gardens (1994)

FIND IT ON THE MAP

It’s commonly assumed that Landscape Architecture as a discipline was conceived by Frederick Law Olmsted in the second half of the Nineteenth Century when he incorporated, with the help of the English architect Calvert Vaux, the tradition and techniques of nursery, agriculture, and gardening to the rampant growth of the North American Cities. We must say too that Olmsted was a mature person when he started that venture. Before he spent an important part of his time working as a journalist so, he was an excellent narrator and polemist. That’s why we have a wide written report of his thoughts and his works that constitutes an exceptionally rich theory, that sometimes has a surprising smell of contemporaneity.

Judith Stilgenbauer, Processcapes: Dynamic Placemaking (2015)

Peter Walker + PWP Landscape Architecture, Hilton Hotel (former Kempinski) Gardens (1994)

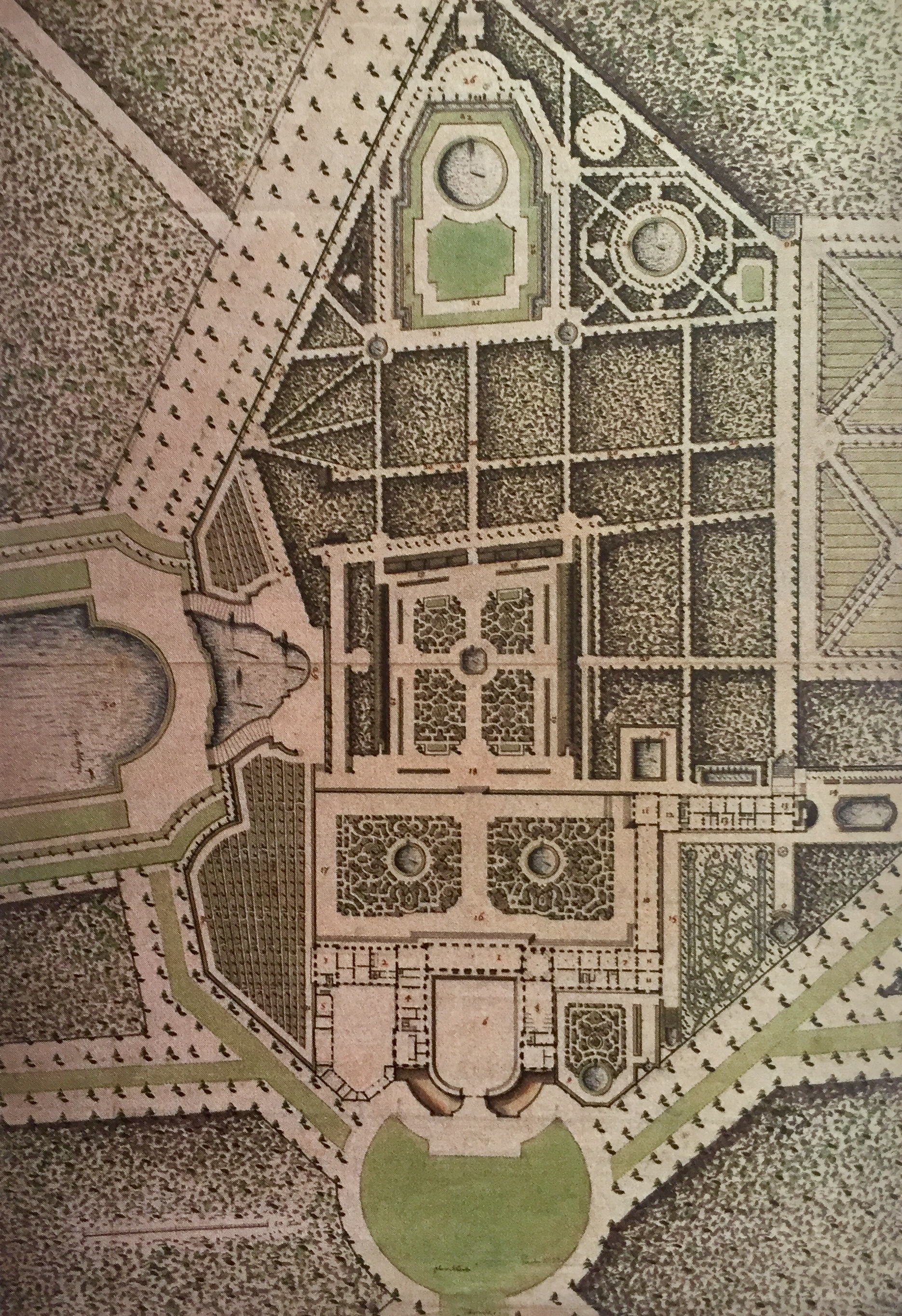

More abstractly, the rise of informality in garden design coincides with a growing interest in empiricism. A devotion to rational geometry gave way to careful observation of the apparent irregularities of the natural world. The serpentine ‘line of beauty’ identified in William Hogarth’s “The Analysis of Beauty” much resembles the serpentine curves of a Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown lake. In the middle of the century, Brown (1716-83) was ascendant and he remains the best-remembered of his peers, in part because he was so prolific, but also because of his memorable moniker which derives from his habit of telling his patrons, having toured their estates, that he thought he saw ‘capabilities’ in them, his own word for ‘possibilities’ or ‘potential’. Brown’s design formula included the elimination of terraces, balustrades, and all traces of formality; a belt of trees thrown around the park; a river dammed to create a winding lake; and handsome trees dotted through the parkland, either individually or in clumps. Interestingly, Brown did not call himself a landscape gardener. He preferred the terms ‘placemaker’ and ‘improver’, which in many ways are conceptually closer to the role of the modern-day landscape architect than ‘landscape gardener’. (…)

Criticism of Brown began in his own day and intensified after his death. He was criticized in his own time, not for destroying many formal gardens (which he certainly did), but for not going far enough towards nature. Among his detractors were two Hereford squires’ Uvedale Price and Richard Payne Knight, both advocates of the new picturesque style. To count as Picturesque, a view or a design had to be a suitable subject for a painting, but enthusiasts for the new fashion were of the opinion that Brown’s landscapes were too boring to qualify. Knigts’s didactic poem “The Landscape” was directed against Brown, whose interventions, he said, could only create a ‘dull, vapid, smooth, and tranquil scene’. What was required was some roughness, shagginess, and variety. This is an argument mirrored in today’s opposition between manicured lawns and wildflower meadows. In the United States, where smooth trimmed lawns have been the orthodox treatment for the front yard, often regulated by city ordinances, growing anything other than a well-tended monoculture of grass in front of the house can be controversial.

Ian Thompson, Landscape Architecture. A Very Short Introduction. (2014)

Lancelot “Capability” Brown, Blenheim Estate (1764)

Gardens of all sorts come in all sizes and guises. And our interest in them also takes many approaches. We study the process of their design, their built forms, their materials and plantings, their meanings, their use or how they are experienced on the ground and represented in word and image, their decay and maybe their recuperation. We are interested in who their designers were, who commissioned them, and the motives of both designers and patrons, along with the political and social contexts in which gardens came into being. But sometimes we also construct our own memories of these places.

A history of gardens is best undertaken as a cultural history, even if its primary focus is design, botany, hydraulics or sculpture. People engage in place-making because our choice of habitation is of supreme importance, as we find our identity and a sense of belonging in the process of colonizing and cultivation, which the word ‘culture’ (derived from Latin colere) implies. It is not enough to look at gardens for their style (endlessly and emptily touted as ‘formal’ or ‘informal’, ‘baroque’, ‘picturesque’, ‘arts and crafts’), nor even enough to assess their visual appearance. We need to ask why they came into being, what advantages and pleasures (including the visual, to be sure) accrue from them, and how and why they have survived, changed or vanished.

The range of places that can be envisaged within the category of ‘garden’ is also enormous and various, and it changes from locality to locality, and from age to age. Yet this diversity does not wholly inhibit us from knowing what it is that we want to discuss when we think of gardens. Above all, it is useful to think of the garden as typically a place of paradox, being the work of men and women yet created from elements of nature, the two held in some precious and often precarious tension. And while a garden is often acknowledged to be a ‘total environment’, a place that may be physically separated from other zones, it also answers and displays connections with larger environments and concerns, not least agriculture and cities. Gardens, in short, are both entities within themselves and a focus of human speculations, propositions, and negotiations, concerning what it is to live in the world.

John Dixon Hunt, A World of Gardens (2012)

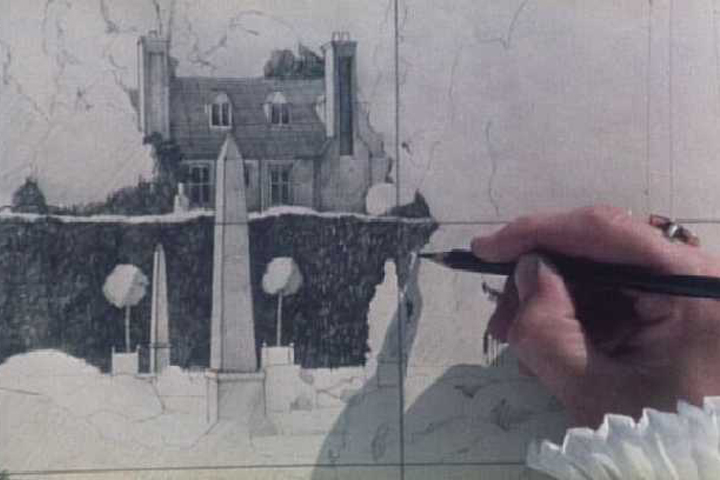

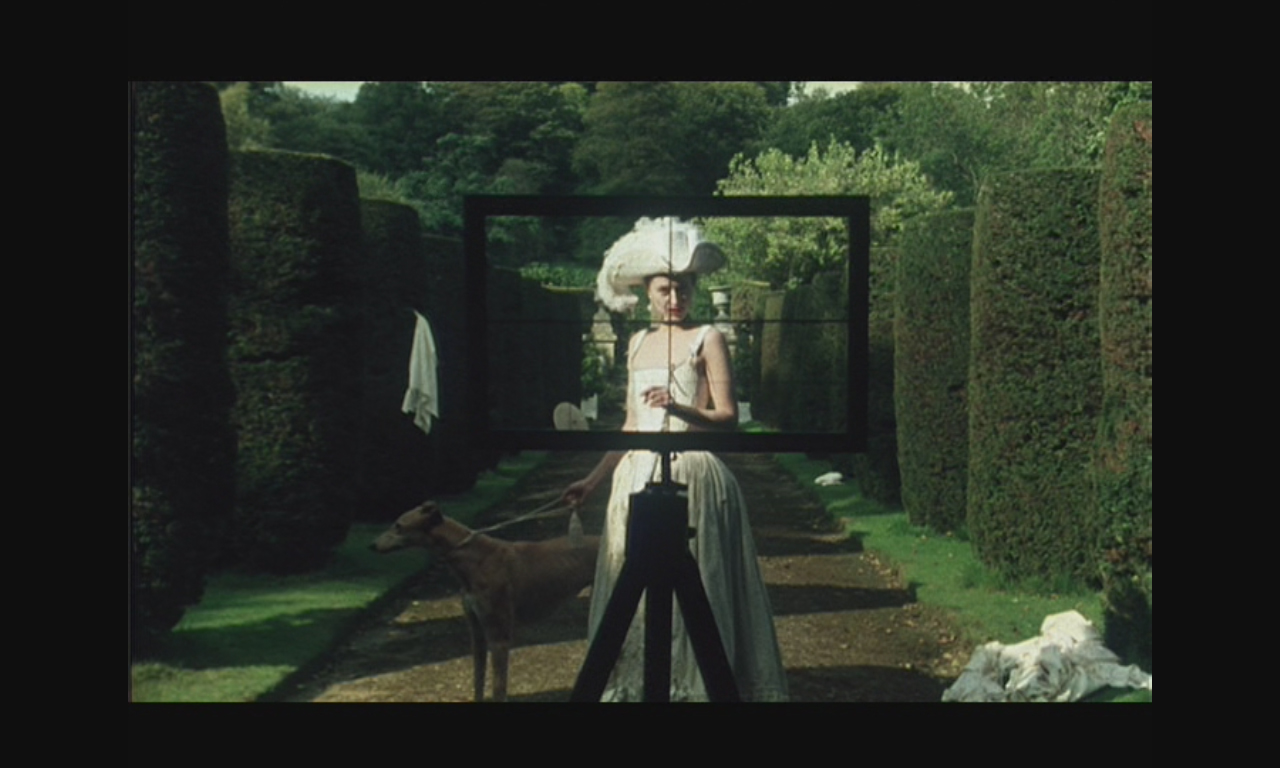

Peter Greenaway, The Draughtsman’s Contract (1982)

John Evelyn, Groombridge Place Estates (circa 1650)

Olmsted employed the term pastoral instead of the beautiful or picturesque to evoke a familiar, tranquil, and cultivated nature as a counterpoint to the city. Olmsted’s pastoral wove together the precepts of eighteenth-century landscape theory and Jeffersonian agrarianism.

Even more than Downing, Olmsted regarded the landscape as an instrument of social order. Gently undulating grass, serpentine lakes, sinuous pathways, and leafy woodland groves provided urban dwellers a much-sought-after alternative to the dense industrial city, presumably with salutary moral as well as physical effects. Not intended as a zone of active use, the pastoral public park presented composed scenery for passive viewing. The purpose of this engagement Olmsted described with typical zeal: “No one who has closely observed the conduct of people who visit Central Park can doubt it exercises a distinctly harmonizing and refining influence upon the most unfortunate and lawless of the city —an influence favorable to courtesy, self-control, and temperance.”

Urban dwellers proved much more resistant to “harmonizing” than Olmsted expected, and in the face of American pluralism, public parks became more diverse in their activities and accommodations. Nevertheless, as reiterations of Central Park appeared in cities large and small across the United States by the beginning of the twentieth century, the enveloping pastoral aesthetic of the public park prevailed and carried with it the equation of pastoral scenery and ameliorative social influence.

Louise Mozingo, Pastoral Capitalism (2011)

Frank Leslie, The Central Park. A delightful resort for the toil-worn New Yorkers (1869)

Header: Frederick Law Olmsted + Calvert Vaux, Map of Central Park, New York City (1868)

So what do we mean by the art of design? I first saw this remarkable design at an exhibition of landscape drawings from 1600-2000 currently on display at Het Loo in Appledoorn. l remarked to my colleagues that it would be wonderful if a student handed in a drawing like that. Wondering who had designed it we peered at the text and found it was by le Notre; it was his design for the gardens of the Grand Trianon at Versailles, accompanied by eight pages of manuscript connecting image and concept, ideas and form.

It is remarkable for many reasons. It exhibits astonishing skill and confidence in the expression of ideas in form, through technology, with elegance and panache. Far from being a slave to the geometry of the plan, the asymmetrical design is an imaginative manipulation of the spatial structure of the landscape, intensifying perspectives, foreshortening views, skewing natural cross falls and creating vistas, connecting seamlessly with the landscape beyond. It is responsive to the topography and context, culture and time. Extraordinarily knowledgeable, skilfully exploiting the full range of the medium, this design is there to manipulate the emotions, express power, and control movement. This is what the art of design is about. There is no mistaking its brilliance – if you know what to look for.

A powerful cultural force is currently undermining any serious attempt to develop the kind of expertise le Notre exhibits. It is, of course, possible to teach many aspects of design. There are books on design theory, criticism, history, its technology and modes of communication. There are guides on collaboration, team building and how to carry out design reviews. But large chunks of the actual design process, the real nitty-gritty of the discipline, are clouded by subjectivity and therefore thought to be beyond teaching. Design is often characterized as a highly personal, mysterious act, almost like alchemy, adding weight to the dangerous idea that it is possible, even preferable, to hide behind the supposed objective neutrality implied by more ‘scientific’, technology-based, problem-solving approaches. Talking about excellence is actually considered somehow undemocratic and elitist. It is this kind of dogmatism that impacts so negatively on our thinking about design.

Kathrin Moore, Overlooking the Visual. Demystifying the art of Design. (2010)

André le Nôtre, Design for the gardens of the Grand Trianon (1694). Stockholm National Museum of Fine Art.

Landscape urbanism is often heralded as the saviour of the built professions, as the new –ism with concerns that are congruent with the politically correct, ecological biases and priorities of the developed, Western world. Much of the contemporary discourse on landscape urbanism – and the projects aligned with this emerging field – focus upon the challenges posed by post-industrial urban voids. The recovery of brownfield sites and the reintroduction of natural processes and habitats are key issues linked to landscape urbanism. At the same time, it is arguable that such projects are more landscape architecture – as opposed to landscape urbanism. Often, the urbanism component is lacking.

This paper will develop an argument that landscape urbanism – understood as structuring landscapes to guide their occupation, use and urbanization – is not new, but has indeed been in practice for several millennia. It argues that there is an ancient, indigenous landscape urbanism whereby an integral system of urbanization is tied to the logics of landscapes. More specifically, it investigates territories structured by water resource management and the relationship of such landscapes to urbanization.

Angammedilla Gal Amuna (Rajabemma) at Polonnaruwa (ca 1175)

Initial capitals have been used in the account of Knight, Price and Repton for the words Beautiful, Sublime and Picturesque, to mark their use as part of a specialised aesthetic vocabulary. As explained by Edmund Burke, ‘Beautiful’ meant smooth, flowing, like the body of a beautiful woman. ‘Sublime’ meant wild and frightening, like a rough sea or the views that might be obtained while crossing the Alps on a rocky track in a horsedrawn coach. ‘Picturesque’ was an intermediate term, introduced after Burke, to describe a scene with elements of the Beautiful and the Sublime. Without its initial capital, ‘Picturesque’ means ‘like a picture’. In what is called the landscape style in this book, Picturesque gardens have a sequential transition from a Beautiful foreground, through a Picturesque middle ground to a Sublime background. Composing gardens like paintings integrated the design ideas of the eighteenth century to create a landscape design concept of significant grandeur and exceptionally wide application.

The landscape style is the chief support for the claim that British designers made a unique contribution to western culture during the eighteenth century. In his 1955 Reith Lectures Nikolaus Pevsner used the term ‘English picturesque theory’ for what he described as an ‘English national planning theory’. Pevsner stated that it ‘lies hidden in the writings of the improvers from Pope to Uvedale Price, and Payne Knight’ and that it gave English town planners ‘something of great value to offer to other nations’. He then asked whether the same can be said ‘of painting, of sculpture, and of architecture proper’. His answer was that Henry Moore and other sculptors had ‘given England a position in European sculpture such as she has never before held’, but that English painting and architecture of the period were of markedly lower quality.

Tom Turner, Garden History (2005)

Humphry Repton, Woburn Abbey Gardens (1805)

FIND IT ON THE MAPThe breadth of knowledge demonstrated by Frederick Law Olmsted, Charles Eliot, and other pioneers in designing and planning the land continues to amaze me. They seemed to have studied and rigorously understood biology, the physical environment, aesthetics, and socioeconomics. They successfully tied together nature protection, recreation, sewage treatment, transportation, land restoration, visual quality, solid waste disposal, and water quality. Amazing!

Today society and the land desperately need designers and planners, or some other knowledgeable group, to step forward onto the broad solid shoulders of those giants. Ecologists, economists, and engineers obviously contribute in major ways. But today each has too few of the tools needed to create a sustainable synthesis of nature and culture. Meanwhile, most landscape designers are inspired by and primarily focused on important aesthetic dimensions, leaving society’s other major objectives to secondary status. And most planners today highlight important economics or public policy dimensions, leaving lesser status to other key societal objectives. Not surprisingly, I salute the impressive exceptions to these general patterns. Also, clearly, each field evolves over time, and today each has its vision of sustainability.

Nevertheless, this leaves society with tough questions: Is landscape design now largely peripheral to the major concerns of society? Is planning now largely enmeshed in the economic and governmental status quo? Is society now degrading landscapes and land at an accelerating pace? Do we hear the environmentalists’ crescendo calling for a sustainable future for land and people?

“Yes” resounds for all four questions. Yet I believe that design and planning have the potential to make a difference for land and people. Indeed, the footsteps of a vanguard of emerging leaders, outlining a new design and planning field, can be heard. Some have their names in this book.

Three key steps are needed to reach this new level.

First, the science of ecology must become a central foundation of design and planning. This will noticeably strengthen the field. But it also makes this the only discipline with a palette of expertise effectively embracing both natural systems and human culture.

Second, theory must become clearly stated and put to use in design and planning. That is, the central body of principles needs to be delineated and refined, both to solidify the field and to underpin dependable practice.

Third, boldness must become the norm. Boldness is an alternative to tinkering or the status quo, not a license that “anything goes.” Rather, to alter the dominant direction of human land-use change that is so detrimental to long-term nature and culture, boldness requires either a multitude of minor changes or a major new vision. In either case, the proposed solution must be sufficiently understandable and beneficial to society that it has real potential to spread widely in the near future. Neither a few minor changes nor an idiosyncratic new vision holds promise for accomplishing this objective. Assuming a major role in society requires stepping forward with bold new solution.

Richard T. T. Forman, The Missing Catalyst: Design and Planning with Ecology Roots (2002)

Frederick Law Olmsted, Calvert Vaux & Co., Riverside (1869)

Frederick Law Olmsted, Emerald Necklace (1878-1894)

The word itself tells us much. It entered the English language, along with herring and bleached linen, as a Dutch import at the end of the sixteenth century. And landschap, like its Germanic root, Landschaft, signified a unit of human occupation, indeed a jurisdiction, as much as anything that might be a pleasant object of depiction. So it was surely not accidental that in the Netherlandish flood-fields, itself the site of formidable human engineering, a community developed the idea of a landschap, which in the colloquial English of the time became a landskip. Its Italian equivalents, the pastoral idyll of brooks and wheat-gold hills, were known as parerga, and were the auxiliary settings for the familiar motifs of classical myth and sacred scripture. But in the Netherlands, the human design and use of the landscape -implied by the fishermen, cattle drovers, and ordinary walkers and riders who dotted the painting of Esaias van de Velde, for example- was the story, startlingly sufficient unto itself.

Simon Shama, Landscape and Memory (1995)

Strootman Landschapsarchitecten, Belvederes Drentsche Aa (2010)

I am all the time bothered with the miserable nomenclature of L. A. Landscape is not a good word, Architecture is not; the combination is not — Gardening is worse. I want English names for ferme and village ornee, street. ornee — but ornee or decorated is not the idea, — it is artified and rural artified, which is not decorated merely. The art is not gardening nor is its architecture. What I am doing here in California especially is neither. It is sylvan art, fine art in distinction from Horticulture, Agriculture, or sylvan useful art. We want a distinction between a nurseryman or a market gardener or an orchardist, and an artist; the planting of a street or road, the arrangement of village streets, is neither Landscape Art, nor Architectural Art, nor is it both together in my mind, — of course it is not, and it will never be in the popular mind. Then neither park nor garden, nor street, road, avenue, or drive, nor boulevard, apply to a sylvan bordered and artistically arranged system of roads, sidewalks and public places, — playgrounds, parades, etc. (…)

If you are bound to establish this new art, you don’t want an old name for it. And for clearness, for convenience, for distinctness, you do need half a dozen technical words at least.

Frederick Law Olmsted, Letter to Calvert Vaux (1865)

Say it again: landscape architecture. The words roll off the tongue as if their union were inevitable. But this is an arranged marriage. Most landscape practitioners know the name doesn’t quite fit, though few give it further thought. If it hasn’t stopped the production of innovative work, they reason, where is the harm? The crucial question is whether the apparent alliance of landscape and architecture conceals other possibilities for how these two parties might relate to each other, and how they might relate to the world.

Brian Davis & Thomas Oles, From Architecture to Landscape (2014)

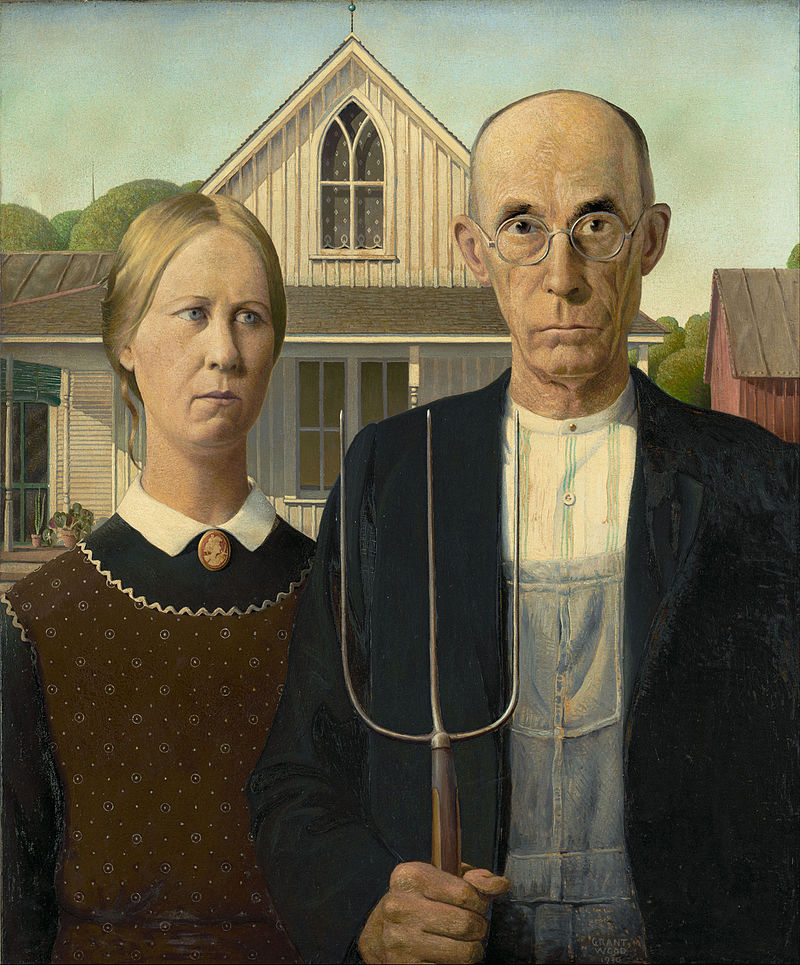

Grant Wood, American Gothic (1930)

Grant Wood, The Birthplace of Herbert Hoover (1931)

Grant Wood, Young Corn (1931)

Grant Wood, Stone City (1930)