All landscape is reuse, whether through the intervention of human action or through the earth’s continual formation in a process that, in the words of geologist James Hutton, ‘has no vestiges of a beginning, nor prospects of and end’. Acting in parallel, human and non-human agents work to remake the surface of the earth and its ecosystems, though on different material and temporal scales and with different impacts, often working against each other. Thus, it is not possible to ‘discard’ landscape, only to reuse it. Continual formation and reformation is central to Georg Simmel’s definition of landscape. In his 1913 essay ‘Philosophy of Landscape’, he defines it as a subset of that which is not divisible: nature. In the tension between landscape’s claim for autonomy against ‘the infinite interconnectedness of objects, the uninterrupted creation and destruction of forms’, a boundary, says Simmel, is essential. In this essay I posit that to construct this tension between the discrete and the continuous, and to make its representation visible, is both the work of design and the work of criticism in the age of global disruption.

In the intervening century since the publication of Simmel’s essay, capitalism has advanced to form a globally interconnected and undifferentiated world. Many boundaries have disappeared while others have been formed as economies and priorities shift, as the strength of the institutions that sanction landscape wanes, as nature’s entropic forces soften its structures. Still, it must be emphasized, landscapes continue to be an act of will, a social product that registers the conflicts, the diverse interests, the tensions and the pressures that act on it. As such, landscapes do not just appear on their own, they must be simultaneously created, kept, maintained, and protected through institutions and governance. In this way they are demarcated, strongly or more subtly.

Anita Berrizbeitia, Criticism in the age of global disruption (2018)

Martí Franch + EMF, Jordi Badia + BAAS, Can Framis Museum Gardens (2009)

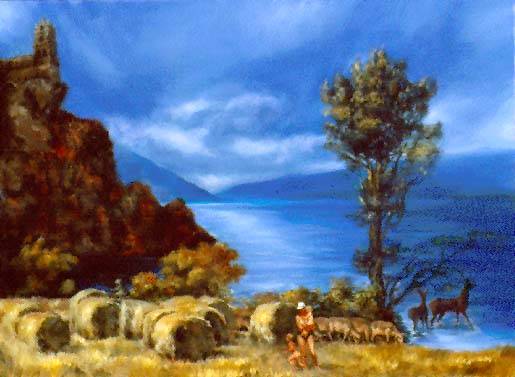

Komar and Melamid, Russia’s Most Wanted Painting (1995)

Komar and Melamid, Russia’s Most Wanted Painting (1995) Komar and Melamid, China’s Most Wanted Painting (1995)

Komar and Melamid, China’s Most Wanted Painting (1995) Komar and Melamid, France’s Most Wanted Painting (1995)

Komar and Melamid, France’s Most Wanted Painting (1995) Komar and Melamid, Germany’s Most Wanted Painting (1995)

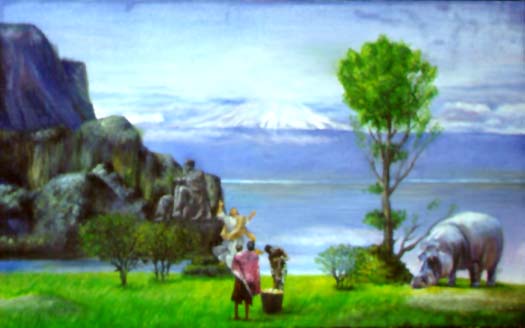

Komar and Melamid, Germany’s Most Wanted Painting (1995) Komar and Melamid, Kenya’s Most Wanted Painting (1995)

Komar and Melamid, Kenya’s Most Wanted Painting (1995) Komar and Melamid, Italy’s Most Wanted Painting (1995)

Komar and Melamid, Italy’s Most Wanted Painting (1995) Komar and Melamid, Holland’s Most Wanted Painting (1995)

Komar and Melamid, Holland’s Most Wanted Painting (1995)