Judith Stilgenbauer, Processcapes: Dynamic Placemaking (2015)

Peter Walker + PWP Landscape Architecture, Hilton Hotel (former Kempinski) Gardens (1994)

FIND IT ON THE MAP

(1822-1903) American landscape architect considered the founder of the Landscape Architecture discipline.

Judith Stilgenbauer, Processcapes: Dynamic Placemaking (2015)

Peter Walker + PWP Landscape Architecture, Hilton Hotel (former Kempinski) Gardens (1994)

Olmsted employed the term pastoral instead of the beautiful or picturesque to evoke a familiar, tranquil, and cultivated nature as a counterpoint to the city. Olmsted’s pastoral wove together the precepts of eighteenth-century landscape theory and Jeffersonian agrarianism.

Even more than Downing, Olmsted regarded the landscape as an instrument of social order. Gently undulating grass, serpentine lakes, sinuous pathways, and leafy woodland groves provided urban dwellers a much-sought-after alternative to the dense industrial city, presumably with salutary moral as well as physical effects. Not intended as a zone of active use, the pastoral public park presented composed scenery for passive viewing. The purpose of this engagement Olmsted described with typical zeal: “No one who has closely observed the conduct of people who visit Central Park can doubt it exercises a distinctly harmonizing and refining influence upon the most unfortunate and lawless of the city —an influence favorable to courtesy, self-control, and temperance.”

Urban dwellers proved much more resistant to “harmonizing” than Olmsted expected, and in the face of American pluralism, public parks became more diverse in their activities and accommodations. Nevertheless, as reiterations of Central Park appeared in cities large and small across the United States by the beginning of the twentieth century, the enveloping pastoral aesthetic of the public park prevailed and carried with it the equation of pastoral scenery and ameliorative social influence.

Louise Mozingo, Pastoral Capitalism (2011)

Frank Leslie, The Central Park. A delightful resort for the toil-worn New Yorkers (1869)

Header: Frederick Law Olmsted + Calvert Vaux, Map of Central Park, New York City (1868)

The urban park was a 19th-century concept, its invention necessary to provide relief to the urban victims of the new, untamed metropolis. (…) Planning, real estate development, and the poetic presence of nature were combined. Properly regarded, these were the purest forms of landscape urbanism—or landscape-as-infrastructure.

This Olmstedian principle seems still to be the ideal of landscape urbanism, although in practice hardly any critical attention is paid to some of its weaker aspects. Why is it so easily taken for granted that the green of parks will bring a better world?

First, the steadily increasing area of suburban green structures is of a dubiously hybrid character: they are often loud statements of overdesigned park architecture expressing a desire for liveliness, and for the cultural significance of beloved 19th-century city parks; but on the other hand, they attempt to create an idealistic wilderness. Realization of these plans often results in a strange nonworld of cultivated innocence. The essential characteristics a park needs to survive, so exhaustively described by Jane Jacobs, are almost always lacking. According to her analysis, for parks and greenery to succeed, a good context is fundamental. Many city dwellers see peripheral green zones as valuable green background, but also as potentially dangerous, and as places to be avoided. There is simply too little activity and no mixing of user groups. Park designers have not succeeded in giving these parks the allure of nature and wilderness.

Second, landscape architecture is fundamentally linked to nature, to mother earth. But the perception of “nature” is a cultural phenomenon, quite different from one country to another. The elemental forces of nature have also, through prosperity or privation, shaped behavioral second natures— yielding national identities, religions, livelihoods, and even wars. From these basic conditions cultures are formed, each with its particular perceptions of nature. When you talk with di erent nationalities about nature, you are confronted by deeply rooted feelings and cultural convictions, all of which are assumed to be a matter of “common sense.”

Finally, the pretension often is that parks are the result of ideology and craftsmanship, and are therefore inherently unique and valuable. However, landscape architecture, in contrast to architecture, is concerned almost exclusively with the public realm—parks, boulevards, riverfronts, streetscapes, and so on. To reach decisions and establish nances, we must work with politicians, local citizens, and bureaucracies with diverse legal systems. Landscape architecture will always focus on outreach, public opinion, interaction, public policy, implementation, and compromise. The discipline cannot avoid responding to sociopolitical contexts.

Economists have an acronym to identify the forces driving development: PESTEL (politics, economics, sociology, technology, environment, and law). It is critically important that contemporary planning initiatives explicitly take these factors into account. Clearly such diverse issues as governance and legislation, high- and low-tech implementation strategies, grassroots advocacy, and megaprojects all are attendant on public policy. So in practice landscape architects and park designers work in a realm between illusion and public policy, and our work is inevitably the most banal and compromised among the design disciplines. At the end of the day, are the built realities anywhere close to the dreamt-of parks and artist’s impressions?

SWA Group, Ningbo East New Town Eco-Corridor (2013-)

Hypernature: the recognition of art

The recognition of art is fundamental to, and a precondition of landscape design.

This is not a new idea; nineteenth-century landscape design theorists J.C. Loudon, A.J. Downing and Frederick Law Olmsted advocated as much when making the case for the inclusion of landscape design or landscape architecture as one of the Fine Arts. More recently, Michael Van Valkenburgh and his partners, Laura Solano and Matthew Urbanksi, expressed their interest in exaggerated, concentrated hypernature – an exaggerated version of constructed nature. Creating hypernature was prompted by pragmatic acknowledgements of the constrictions of building on tough urban sites and the recognition that designed landscapes are usually experienced while distracted, in the course of everyday urban life. Attenuation of forms, densification of elements, juxtaposition of materials, intentional discontinuities, formal incongruities -tactics associated with montage or collage- are deployed for several reasons: to make a courtyard, a park, a campus more capable of appearing, of being noticed, and of performing more robustly, more resiliently.

Sustainable landscape design should be form-full, evident and palpable, so that it draws the attention of an urban audience distracted by daily concerns ofwork and family, or the over-stimulation of the digital world.

This requires a keen understanding of the medium of landscape, and the deployment of design tactics such as exaggeration, amplification, distillation, condensation, juxtaposition, or transposition/displacement.

Elizabeth K. Meyer, Sustaining Beauty (2008)

Michael Van Valkenburgh, Teardrop Park (2009)

The breadth of knowledge demonstrated by Frederick Law Olmsted, Charles Eliot, and other pioneers in designing and planning the land continues to amaze me. They seemed to have studied and rigorously understood biology, the physical environment, aesthetics, and socioeconomics. They successfully tied together nature protection, recreation, sewage treatment, transportation, land restoration, visual quality, solid waste disposal, and water quality. Amazing!

Today society and the land desperately need designers and planners, or some other knowledgeable group, to step forward onto the broad solid shoulders of those giants. Ecologists, economists, and engineers obviously contribute in major ways. But today each has too few of the tools needed to create a sustainable synthesis of nature and culture. Meanwhile, most landscape designers are inspired by and primarily focused on important aesthetic dimensions, leaving society’s other major objectives to secondary status. And most planners today highlight important economics or public policy dimensions, leaving lesser status to other key societal objectives. Not surprisingly, I salute the impressive exceptions to these general patterns. Also, clearly, each field evolves over time, and today each has its vision of sustainability.

Nevertheless, this leaves society with tough questions: Is landscape design now largely peripheral to the major concerns of society? Is planning now largely enmeshed in the economic and governmental status quo? Is society now degrading landscapes and land at an accelerating pace? Do we hear the environmentalists’ crescendo calling for a sustainable future for land and people?

“Yes” resounds for all four questions. Yet I believe that design and planning have the potential to make a difference for land and people. Indeed, the footsteps of a vanguard of emerging leaders, outlining a new design and planning field, can be heard. Some have their names in this book.

Three key steps are needed to reach this new level.

First, the science of ecology must become a central foundation of design and planning. This will noticeably strengthen the field. But it also makes this the only discipline with a palette of expertise effectively embracing both natural systems and human culture.

Second, theory must become clearly stated and put to use in design and planning. That is, the central body of principles needs to be delineated and refined, both to solidify the field and to underpin dependable practice.

Third, boldness must become the norm. Boldness is an alternative to tinkering or the status quo, not a license that “anything goes.” Rather, to alter the dominant direction of human land-use change that is so detrimental to long-term nature and culture, boldness requires either a multitude of minor changes or a major new vision. In either case, the proposed solution must be sufficiently understandable and beneficial to society that it has real potential to spread widely in the near future. Neither a few minor changes nor an idiosyncratic new vision holds promise for accomplishing this objective. Assuming a major role in society requires stepping forward with bold new solution.

Richard T. T. Forman, The Missing Catalyst: Design and Planning with Ecology Roots (2002)

Frederick Law Olmsted, Calvert Vaux & Co., Riverside (1869)

Frederick Law Olmsted, Emerald Necklace (1878-1894)

Thus, at no great distance from any point of the town, a pleasure ground will have been provided for, suitable for a short stroll, for a playground for children and an airing ground for invalids, and a route of access to the large common park of the whole city of such a character that most of the steps on the way to it would be taken in the midst of a scene of sylvan beauty, and with the sounds and sites of the ordinary town business, if not wholly shut out, removed to some distance and placed in obscurity. The way itself would thus be more park-like than town-like.

Frederick Law Olmsted, Report on The Buffalo Park System (1968)

Header: Frederick Law Olmsted & Calvert Vaux, Buffalo’s Park System and Park-ways, (1868 -1896)

I am all the time bothered with the miserable nomenclature of L. A. Landscape is not a good word, Architecture is not; the combination is not — Gardening is worse. I want English names for ferme and village ornee, street. ornee — but ornee or decorated is not the idea, — it is artified and rural artified, which is not decorated merely. The art is not gardening nor is its architecture. What I am doing here in California especially is neither. It is sylvan art, fine art in distinction from Horticulture, Agriculture, or sylvan useful art. We want a distinction between a nurseryman or a market gardener or an orchardist, and an artist; the planting of a street or road, the arrangement of village streets, is neither Landscape Art, nor Architectural Art, nor is it both together in my mind, — of course it is not, and it will never be in the popular mind. Then neither park nor garden, nor street, road, avenue, or drive, nor boulevard, apply to a sylvan bordered and artistically arranged system of roads, sidewalks and public places, — playgrounds, parades, etc. (…)

If you are bound to establish this new art, you don’t want an old name for it. And for clearness, for convenience, for distinctness, you do need half a dozen technical words at least.

Frederick Law Olmsted, Letter to Calvert Vaux (1865)

Say it again: landscape architecture. The words roll off the tongue as if their union were inevitable. But this is an arranged marriage. Most landscape practitioners know the name doesn’t quite fit, though few give it further thought. If it hasn’t stopped the production of innovative work, they reason, where is the harm? The crucial question is whether the apparent alliance of landscape and architecture conceals other possibilities for how these two parties might relate to each other, and how they might relate to the world.

Brian Davis & Thomas Oles, From Architecture to Landscape (2014)

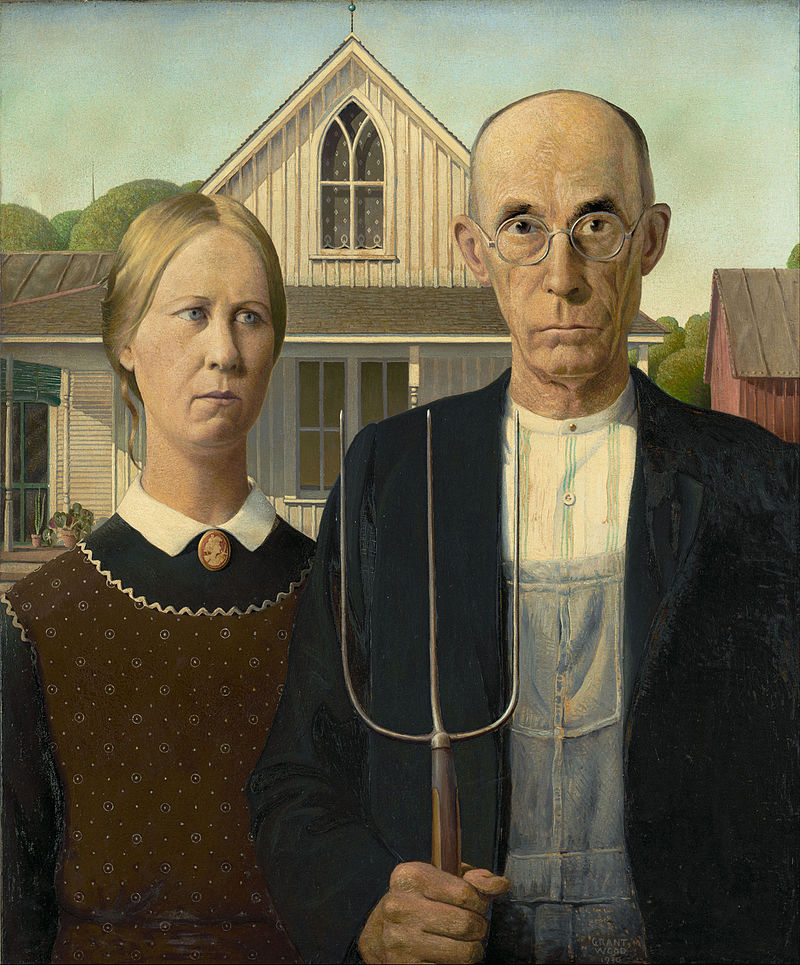

Grant Wood, American Gothic (1930)

Grant Wood, The Birthplace of Herbert Hoover (1931)

Grant Wood, Young Corn (1931)

Grant Wood, Stone City (1930)

It therefore results that the enjoyment of scenery employs the mind without fatigue and yet exercises it; tranquilizes it and yet enlivens it; and thus, through the influence of the mind over the body, gives the effect of refreshing rest and reinvigoration to the whole system.

Men who are rich enough (…) can and do provide places of this needed recreation for themselves. They have done so from the earliest periods known in the history of the world, for the great men (…) had their rural retreats (…) private parks and notable grounds devoted to luxury and recreation (…) The enjoyment of the choicest natural scenes in the country and the means of recreation connected with them is thus a monopoly, in a very peculiar manner, of a very few, very rich people. The great mass of society, including those to whom it would be of the greatest benefit, is excluded from it (…).

Thus without means are taken by government to withhold them from the grasp of individuals, all places favorable in scenery to the recreation of the mind and body will be closed against the great body of the people. For the same reason that the water of rivers should be guarded against private appropriation and (…) obstruction, portions of natural scenery may therefore properly be guarded and cared for by government. To simply reserve them from monopoly by individuals, however, it will be obvious, is not all that is necessary. It is necessary that they should be laid open to the use of the body of the people.

The establishment by government of great public grounds for the free enjoyment of the people under certain circumstances, is thus justified and enforced as a political duty.

Frederick Law Olmsted, America’s National Park System: The Critical Documents (c.1864)

Seeking for the declaration of the first National Park, the protection of Yosemite Valley is presented as the democratization of the freeing values of untouched natural scenery. Is not a question about a freedom shaped by the God’s work, but to the contrary, a freedom born in the absence of society’s transformation of the world. So, Olmsted fosters and uses a big American tradition that goes from Emerson and Thoreau to nowadays. From this point of view, nature is seen as a relief for the mind itself of an essential evil: society and the city. This puts all the rest of Olmsted’s work in a troubled position because living in the city become something that must be regulated and controlled in the times of the big urban growth, and be paradoxically defended by uneducated people, the ones that come from natural contexts (see Landscape as an Instrument of Social Order)

Apple, Os X Yosemite Image (2014)

Header: Ansel Adams, Clearing Winter Storm (1937)

I ever saw that has been really built at all in accordance with the advanced science, taste, and enterprising spirit that are supposed to distinguish the nineteenth century. I happen to observe them. Certainly, in what I have noticed, it is a model town, and may be held up as an example, not only to philanthropists and men of taste, but to speculators and men of business.

Frederick Law Olmsted, The People’s Park at Birkenhead (1851)

Joseph Paxton, Park at Birkenhead (1847)

Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted’s Central Park, as viewed from Rockefeller Center (1936)