Category: aesthetics

Besides other questions related to a troubled world there is still there the quest for beauty in landscape theory

Social Agenda

It is in his social agenda that Burle Marx’s lectures are perhaps most surprising. In several lectures Burle Marx tells us that he is motivated by people, by the collective, and by society. While this is very much consistent with his role as an activist, the general perception of Burle Marx’s landscape architecture was that he did not care about the client or user, but did his own thing. Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe put it bluntly, “You see, what he does is he will walk onto a site and do the swishing and do these lovely things, mind it will be his thing, it will be what he wants to have there and very nice worthwhile it is too.” Even Haruyoshi Ono would confirm this approach: that Burle Marx did what he himself wanted, but that over time he began to consider the user more carefully. “In the beginning before I started to work with Roberto, he just said ‘I think I want this garden’ and made it. But then I started to work with him and tried to, more or less, open his mind and said ‘you have to listen to the client because the garden is for the client.’ Then he became more open for the client.”

In Finding a Garden Style to Meet Contemporary Needs, Burle Marx tells us that, “a work of art cannot be, I think, the result of a haphazard solution.” He applied what he termed a series of principles-not formulas-to his projects. He claims in Concepts in Landscape Composition, to have ‘never deliberately sought originality as an aim.” Having been initially trained as a painter -who works alone- Burle Marx brought the attitude of the “great maestro” to his landscape architecture, even though, through his firm, he provided full-service design, from concept to maintenance. Despite -or indeed because of- his concern for the users, and their quality of life and their needs, he believed very much in the agency of design. In Gardens and Ecology he tells us, “The social mission of the landscape architect has a pedagogical side of communicating to the masses a feeling of esteem and comprehension of the values of nature through his presentation of it in parks and gardens.” Burle Marx saw the potential of design to educate on the environment, in addition to the ability of changing the quality of lives through his landscape architecture. Burle Marx’s lectures show the social intentions of his artistry.

Gareth Doherty, On Burle Marx and his Lectures (2018)

Roberto Burle-Marx, Copacabana Promenade (1970)

FIND IT ON THE MAP

Connection

The practical measures of sustainable design make the landscape function more efficiently and reduce the amount of wasted materials and energy; they are conceived to contribute to the overall health of the planet rather than detract. But without an artistic or cultural component to the landscape, we are creating natural places that function like machines. A truly sustainable place works on a more visceral level. We are transforming places so people will love them, will take better care of them, will want them to flourish for their grandchildren and their grandchildren’s grandchildren. If we just look at what are called “best practices,” meaning the technologies that are accepted as most environmentally healthful, we still would not necessarily know how to make a landscape that people will internalize, make their own. Sustainability is about people taking ownership, learning how to sustain, rather than abuse or just consume, the landscape. It is about making clear the connection between human practices and our environment.

The field of landscape architecture can make these connections between humans and our environment.

Joao Ferreira Nunes + Proap, Alcantara Wastewater Treatment Plant (2011)

FIND IT ON THE MAP

Models

We are living in intellectually troubled times for landscape architecture. Part of the reason for the awkwardness in the present debate is not only due to imminent environmental degradation, but also to the rapid degeneration of our own symbolic understanding of nature. We are the receptacles of models of thinking inherited from our forefathers, and when it comes to nature, these models seriously hamper our actual perception of things. What we find out there has little to do with much of the idealized landscape preconceptions we carry. Older landscape models work effectively, only as ideals, with a deeply warped reception and conception of nature, which in turn, has measurable repercussions on the way we act upon the world. It is my belief that we should start to investigate possible options for a renewed relationship with nature that could also foster a new kind of landscape architecture, defending stronger cultural values of beauty and harmony.

Christophe Girot, Immanent Landscape (2013)

FIND IT ON THE MAP

Amorphous

Landscape has -we saw many images- a bit of an amorphous image. When people think about landscape they don’t think of rigor, of order, of a formal element but rather of something very free, wild and uncontrollable. (…) We never want to reproduce nature or a landscape but we always want to make clear what is tamed, that we use an aesthetic that always works with elements of the landscape -the reason for an “architectural landscape”. That’s why we also create spaces – elements of architecture, for example, spaces, axes, points of high elevation, we create these elements in the landscape as architectural elements, but we always try to work with the contrast between plants and architecture.

Stephan Lenzen, Interview (2012)

Stephan Lenzen + RMP Landschaftsarchitecten, New Gardens in the Dyck Field (2002)

Stephan Lenzen + RMP Landschaftsarchitecten, New Gardens in the Dyck Field (2002)

FIND IT ON THE MAP

Ethics/Aesthetics

Aesthetics are rarely explicitly addressed in conjunction with ethics in the body of literature examining recent landscape architectural research. This seems strange given that, if ‘ecology’ is added to ‘aesthetics’ and ‘ethics’, the classic tripartite definition of the discipline is formulated, and most would agree that this constitutes the unique significance and substance of what we do. (…)

The apparent neglect of research that explicitly addresses aesthetics and ethics together may have several reasons. One aspect is that research paradigms, as well as conventions for working in professional practice, will typically narrow the focus and therefore the methodologies of study or practice. Though often challenged, such crude divisions appear to persist and obstruct the critical development of landscape architectural praxis at all levels. The integrative breadth of landscape architecture is hard to formulate within narrow research and disciplinary specialisms, so when these limitations are overcome landscape theory takes a leap forward. Another aspect contributing to the neglect of detailed aesthetic studies may be the lack of a tradition of philosophical discourse in landscape architecture, coupled with the fact that aesthetics as method, construct, practice, experience and the means toward critical judgment is notoriously hard to define with any rigor. The difficulty in both defining and conveying accurately the nature and significance of aesthetic experience, and in addition, the elusiveness of aesthetic judgment and its tendency to go with the flow of contemporary politics, social taste, and cultural transitions, often means that aesthetics are conveyed tangentially and metaphorically, and sometimes not at all. Many academics are deterred from such intangible topics and tacit approaches, especially the younger in the pursuit of PhDs to whom natural and social science appear to offer greater rigor because they are more amenable to explicit forms of knowledge.

Most Wanted

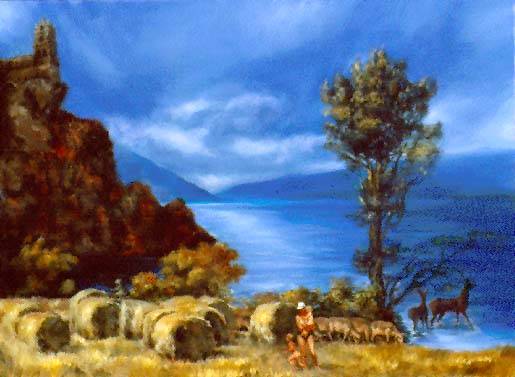

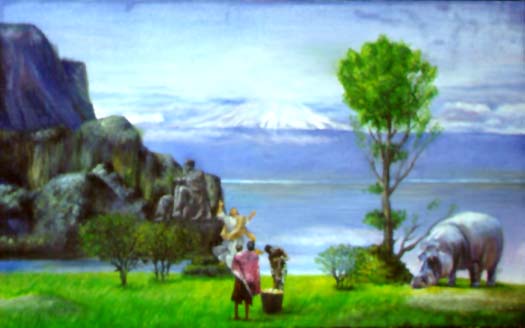

Komar and Melamid are two Russian artist emigrés who undertook a fascinating project. Their book, Painting by Numbers, explains that “with the help of The Nation Institute and a professional polling team, they discovered that what Americans want in art, regardless of class, race, or gender, is exactly what the art world disdains–a tranquil, realistic, blue landscape.”

Once they received the general consensus, they painted the result. The painting above is what Americans prefer to see, complete with a historic figure (George Washington), deer, and children. It’s an ugly amalgamation for sure, but it is quite revealing of the aesthetic preferences of the general populace. One thing that immediately strikes me is that it looks absolutely nothing like what the Art World tells us is ‘good art.’ Although, I do suspect (like Arthur Danto) that most people would rather not actually hang this on their wall. I know I wouldn’t like to.

Not content to stop there, the duo polled countries from all over the World. The results are in (and not a surprise): People the world over tend to prefer a strikingly similar landscape. The elements we have laid out earlier are all there. What does this tell us about aesthetics and human evolution? The argument has been made that the results are an aberration due to the ubiquity of Hallmark calendars in all the countries polled – that the results have been skewed. I like to think that the ubiquity of Hallmark calendars is exactly the proof we’re looking for: Hallmark is everywhere precisely because that’s what we prefer to look at.

Komar and Melamid have just laid out Hallmark’s market research for them, and Evolutionary Psychology has backed it up: The experience of beauty belongs to our evolved human psychology.

Alan Carroll, An Instinct for Beauty (2011)

Komar and Melamid, USA’s Most Wanted Painting (1993)

Komar and Melamid, USA’s Most Wanted Painting (1993) Komar and Melamid, Russia’s Most Wanted Painting (1995)

Komar and Melamid, Russia’s Most Wanted Painting (1995) Komar and Melamid, China’s Most Wanted Painting (1995)

Komar and Melamid, China’s Most Wanted Painting (1995) Komar and Melamid, France’s Most Wanted Painting (1995)

Komar and Melamid, France’s Most Wanted Painting (1995) Komar and Melamid, Germany’s Most Wanted Painting (1995)

Komar and Melamid, Germany’s Most Wanted Painting (1995) Komar and Melamid, Kenya’s Most Wanted Painting (1995)

Komar and Melamid, Kenya’s Most Wanted Painting (1995) Komar and Melamid, Italy’s Most Wanted Painting (1995)

Komar and Melamid, Italy’s Most Wanted Painting (1995) Komar and Melamid, Holland’s Most Wanted Painting (1995)

Komar and Melamid, Holland’s Most Wanted Painting (1995)

Big Nature

Our performance -how we consume, how we waste- is incontrovertibly connected to the state of the environment. We have always had a desirous relation to nature- whether agrarian or industrial, literary or aesthetic. As our technological culture accelerates toward entrepreneurial environments, bonding with Big Nature may come… well, naturally.

Recently, critic and landscape architect Richard Weller pointed out that “landscape architecture is yet to really have its own modernism, an ecological modernity, an ecology free of romanticism and aesthetics”. Because of their functionalism, we are tempted to understand these nexts landscapes as a kind of ecomodernism. But to flourish, they will need to appeal, if not to our sense of romance, at least to our sensibility about how decisions we make today impact the future. We are no longer innocent; contemporary culture is coming to grisps with the Anthropocene epoch, a period that, Nobel Prize-winning chemist Paul Crutzen suggests, began in the late 1700s with the onslaught of fueled human activity.

The onus of our new environmentalism includes a call for an advanced stewardship that is not just about protection or remediation, but an entrepreneurial redefinition of our relationship to nature.

Jane Amidon, Big Nature (2010)

Kongjian Yu + Turenscape, Qunli Stormwater Park (2011)

FIND IT ON THE MAP

Fashionable Ecologism

The beginning of the organic movement had a mistaken attitude, because it didn’t place any emphasis on pleasure. It was an ideological, almost religious approach. It ignored pleasure. Pleasure is not antithetical to health, pleasure is not the enemy of sustainability. Pleasure is moderation, and with moderation we can be sustainable. An environmentalist or an organic farmer that is not also cultivating pleasure is just out of this world.

Examining a number of strategies to popularize environmentalism in the United States, Damien Cave of The New York Times presented a prescient (and humorous) argument for environmental branding in his 2005 article, “It’s Not Sexy Being Green (Yet).” Cave’s essay, in the “Fashion and Style” pages, drew upon the expertise of advertising executives, cultural critics, and environmentalists to, in effect, make being green cool. Reflecting on past environmental crises, Cave recalled the 1970’s as an era of malaise, symbolized by the cardigan sweater President Jimmy Carter wore while delivering his “Crisis of Confidence” speech (1979), a speech that encouraged the general public to reduce their use of energy. This infamous sweater, once denoting lower thermostats and a dwindling energy supply, seems emblematic some twenty-five years later of a challenging and less prosperous time, synonymous with a “righteous denial of fun” and an unfortunate fashion statement. Ironically, Carter was the first president to bring photovoltaic panels to the White House, a fashionable statement of the time that was promptly negated during the Reagan years when they were disassembled.

That environmentalism might escape its sartorial rappings, Cave recognized the need to resituate the green movement for the twenty-first century. Following a number of experts who advocated a newly branded environmentalism -including Earth Day founder, Denis Hayes, who proposed “the easiest way to make something cool is to get cool people to do it”- Cave suggested environmentalism’s spokesperson might need to be a bit sexier than Jimmy Carter, asserting singer Michael Stipe or rapper Mos Def would be better candidates. To this end, Cave advocated the employment of numerous branding strategies, ranging from the use of humor and self-deprecation to irony and satire, even suggesting “conservation needs to become more trendy than a line of sneakers”.

So, why not draw from a broader rank of artists in this quest for coolness? Bruce Sterling, for instance, sci-fi author and founder of the Viridian design movement, could lend his skills in satire, as evidenced by a number of Viridian spoofs including the “Welcome to the Greenhouse” issue of Whole Earth.

Lisa Tider, Ecologies of Access (2010)

Agence Babylone, Riverside Square (2014)

FIND IT ON THE MAP

Role of Beauty

Sustainable landscape design is generally understood in relation to three principles -ecological health, social justice and economic prosperity. Rarely do aesthetics factor into sustainability discourse, except in negative asides conflating the visible with the aesthetic and rendering both superfluous.

This article examines the role of beauty and aesthetics in a sustainability agenda. It argues that it will take more than ecologically regenerative designs for culture to be sustainable, that what is needed are designed landscapes that provoke those who experience them to become more aware of how their actions affect the environment, and to care enough to make changes. This involves considering the role of aesthetic environmental experiences, such as beauty, in re-centering human consciousness from an egocentric to a more bio-centric perspective. This argument in the form of a manifesto is inspired by American landscape architects whose work is not usually understood as contributing to sustainable design.

Elizabeth K. Meyer, Sustaining Beauty (2008)

Piet Oudolf, Hummelo (2017 video)