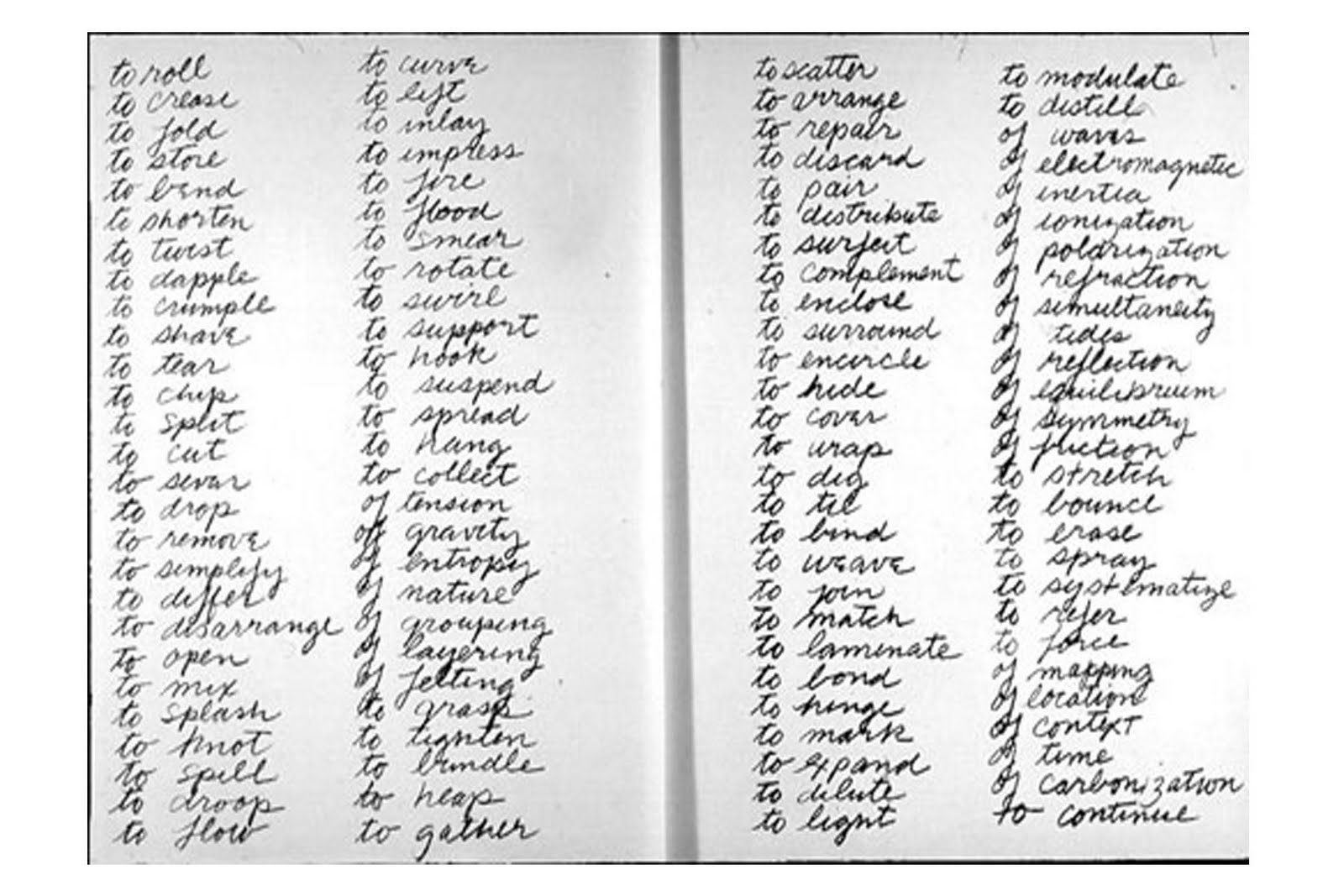

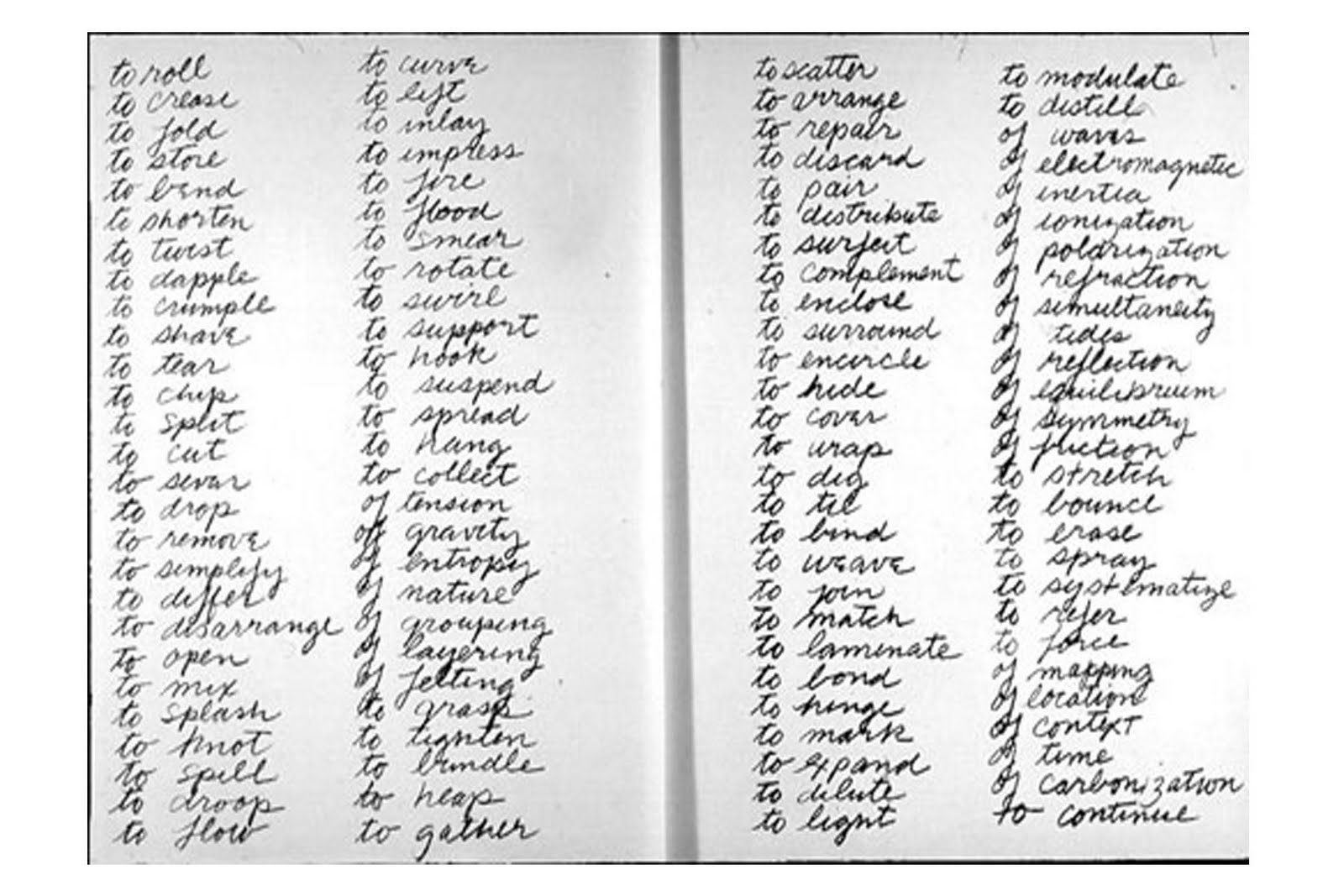

Richard Serra, Verb List (1967-1968)

The “Verb list” established a logic where by the process that constituted a sculpture remains transparent. Anyone can reconstruct the process of the making by viewing the residue.

The sculptures resulting from the “Verb list” introduced two aspects of time: the condensed time of their making and the durational time of their viewing.

Both tasks and materials were ordinary. I was tearing lead in place, lifting rubber in place, rolling and propping lead sheets, and melting lead and splashing it against the juncture between wall and floor. The activities were experimental and playful. It wasn’t the question of how to accomplish this or that, nor was it the question of making it up as I went along: it was rather a free-floating combination of both.

I cannot overemphasize the need for play, for in play you don’t extract yourself from your activity. In order to invent I felt it necessary to make art a practice of affirmative play or conceptual experimentation. The ambiguity of play and its transitional character provides suspension of belief whereby a shift in direction is possible when faced with a complexity that you don’t understand. Free from skepticism, play relinquishes control. Play allows one to accept discontinuities and continuities; it also allows one to happen upon solutions or invent them. However, even in play the task must be carried out with conviction. It’s how we do what we do that confers meaning on what we have done.

Richard Serra, Verb List Commentary (2004)

Richard Serra, Tilted Arc (1981-1989)

Approaching Serra’s art according to its relationship to space leads to the most infamous work of his career, and indeed one of the most important debates about public sculpture in 20th-century art history. It surrounds Tilted Arc (1981), a 12-foot-tall, 120-foot-long wall of curved steel placed across the plaza of the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building in lower Manhattan. Commissioned by the U.S. General Services Administration for its Art-in-Architecture program, Tilted Arc drew criticism from neighboring government employees as soon as it was installed.

By slicing the space of the plaza in half, Tilted Arc served as an obstacle for anyone who wished to traverse it in a straight line. That was Serra’s goal. “Step by step, the perception not only of the sculpture but of the entire environment changes,” he argued, refusing to sanction numerous employees’ requests to have it moved. “To remove the work is to destroy the work.” If moved from the place it was made for, then Tilted Arc would be nothing more than a hunk of steel, Serra said. As a work conceived as “site-specific,” it would cease to be a work of art at all. (Titles of Serra’s work have often paid homage to pioneering site-specific earthwork artists like Robert Smithson and Michael Heizer.)

The dispute swelled until 1985, when a public hearing was held to address legal and philosophical challenges to the work. As taxpayers, did members of the public “own” this art, and if so, why shouldn’t they get to decide what to do with it? Did the First Amendment right to free speech apply to the creation of art? In the end, although 122 of the 180 people who testified voted to retain the sculpture, a jury from the National Endowment for the Arts voted to remove it. Tilted Arc was cut back into three pieces and sent to a storage yard in Brooklyn.

An important episode in the history of public arts patronage, the controversy also helped Serra define his profession. Defending Tilted Arc, he said, “the experience of art itself is a social function.” With echoes of Joseph Beuys’s expanded concept of art as social sculpture (…)

George Philip LeBourdais, How Richard Serra Shaped the Discourse about Public Art in the 20th Century (2016)

After a controversial mobilization against Titled Arc that the world of art will consider as a manipulated one affirming the ability of art to make public be aware of public space appealing to conceptual devices never heard before in Serra’s work, the artist will turn in to a kind of public space fetish. Serra will work in many public spaces all around the world claiming for this awareness that New York had rejected and replaced by a banal installation of a “more human” landscape.

Martha Schwartz, Jacob Javits Federal Building Plaza (1997-2011)

In front of that ambivalent situation, Marta Schwartz project is impregnated of a subtle irony (a virtue not common among landscape architects) because if people complained of the lack of the fluidity of the space when the huge arc was there, it builds a kind of labyrinth that is even worst to the fluidity of the space. But, in the other hand, Schwartz builds a place to be lived, to enjoy an out-of-the-office lunch for example, with soft geometries in front of the cold sky scrappers surroundings following the William H. Whyte research.

Michael Van Valkenburgh, Jacob Javits Federal Building Plaza (2013)

Nevertheless, it’s like if the conflict generated by Titled Arc had generated a popular disease because the Schwartz project won’t last for more than thirteen years before a new project is needed: this time, Michael Van Walkenburg designs with curly lines an invocation to nature. Maybe, at last, is true that Richard Serra’s Arc made people pay attention and claim for a good public space.